Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) is a rare but serious autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its peripheral nerves, leading to muscle weakness, paralysis, and, in severe cases, respiratory failure. While the exact cause of GBS remains unclear, research has identified several triggers and mechanisms associated with its onset. This article explores the leading theories behind the development of GBS and the factors that may contribute to its occurrence.

Autoimmune Basis of GBS

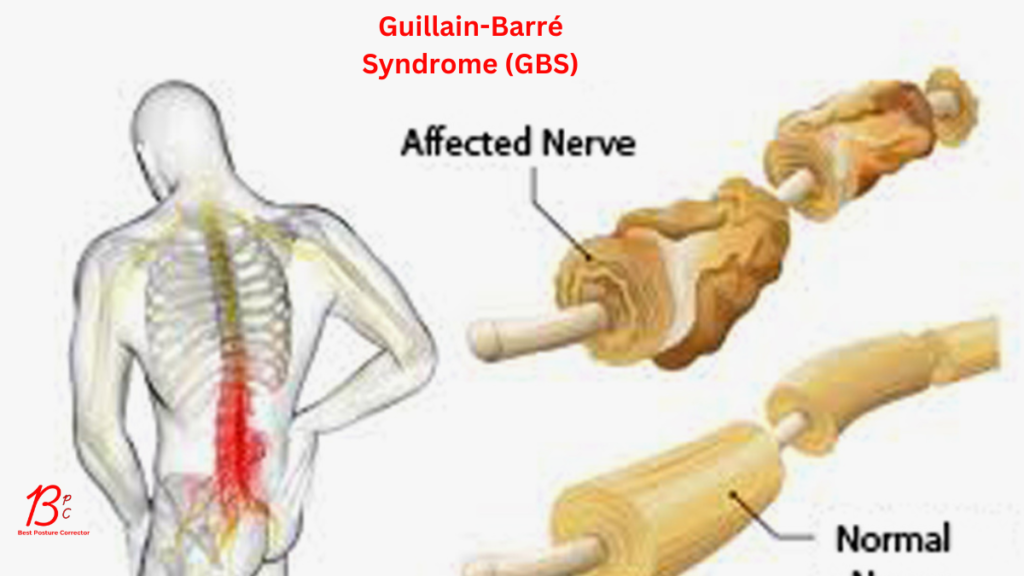

GBS is fundamentally an autoimmune condition. Normally, the immune system defends the body against pathogens like bacteria and viruses. In GBS, however, immune cells and antibodies target the myelin sheath (the protective covering of nerves) or the nerve axons themselves. This disrupts nerve signaling, causing the hallmark symptoms of weakness, numbness, and tingling.

Common Triggers: Infections

Most cases of GBS are preceded by an infection, typically 1–3 weeks before symptoms appear. The immune response to the infection is thought to “misfire,” cross-reacting with nerve tissues. Key pathogens linked to GBS include:

-

Bacterial Infections:

-

Campylobacter jejuni: The most common trigger, often associated with foodborne illness (e.g., undercooked poultry). Up to 40% of GBS cases follow Campylobacter infection.

-

Mycoplasma pneumoniae: A cause of respiratory infections.

-

-

Viral Infections:

-

Epstein-Barr virus (mononucleosis), Cytomegalovirus, and Zika virus.

-

COVID-19: Emerging evidence suggests SARS-CoV-2 infection may increase GBS risk, though this remains rare.

-

Molecular Mimicry: A Key Mechanism

The leading theory for how infections trigger GBS is molecular mimicry. Certain pathogens produce proteins or sugars (antigens) that resemble components of nerve cells. For example, Campylobacter’s surface molecules mimic gangliosides (proteins in nerve membranes). When the immune system attacks the infection, antibodies and immune cells may mistakenly target nerves, causing inflammation and damage.

Vaccinations and GBS

Vaccines are a rare but recognized trigger. The association is not fully understood, but cases are far less common than post-infection GBS. Notable examples include:

-

The 1976 swine flu vaccine (an outlier with a higher GBS risk).

-

The Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines, which reported small increases in GBS risk (approximately 1–2 cases per million doses).

Importantly, the risk of GBS after vaccination is significantly lower than after infections like COVID-19 or Campylobacter.

Other Contributing Factors

-

Surgery or Trauma: Rarely, physical stress from surgery or injury may precede GBS.

-

Genetic Predisposition: Certain genetic markers (e.g., HLA genes) may make some individuals more susceptible to autoimmune triggers.

Conclusion

GBS arises from a complex interplay of environmental triggers and immune dysfunction. Infections, particularly Campylobacter, are the most common culprits, initiating an autoimmune cascade via molecular mimicry. While vaccines and other factors are occasionally implicated, their role is minimal compared to infections. Ongoing research aims to unravel why only a subset of exposed individuals develop GBS, paving the way for better prevention and treatment.

Early diagnosis and therapies like intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasma exchange can significantly improve outcomes, underscoring the importance of seeking prompt medical care for sudden neurological symptoms. Though GBS can be life-altering, most patients recover fully or partially with time and supportive care.

This article reflects current medical understanding as of 2023. Consult healthcare professionals for personalized information.